The Basilica of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. Photo Custoe Terrae Sanctae

History and legend merge within the walls of the Basilica of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, which an ancient tradition identifies as the place of Christ’s crucifixion, burial and resurrection. Built in the 4th century at the behest of Emperor Constantine, destroyed and rebuilt several times, long disputed by different peoples and religious communities, for two thousand years the Basilica has kept the deepest mysteries of Christianity. Today a glimmer seems to open up to its past: the restoration of the medieval floor offers for the first time the possibility of digging underground and reconstructing the history of a multi-thousand-year-old site with the most advanced tools of contemporary archeology.

The project is entirely Italian: while the work on the flooring is entrusted to the “La Venaria Reale” Conservation and Restoration Center in Turin, the excavations are conducted by archaeologists from the Department of Ancient Sciences of the “La Sapienza” University of Rome, at the top of the world rankings in the sector and active on the Palatine Hill as well as in the Middle East, from the ruins of Ebla, in Syria, to the prehistoric city of Arslantepe, in Turkey, which in 2021 received the prestigious Unesco recognition after 60 years of excavations.

Coordinated by the teacher Francesca Romana Stasollathe investigations on the Basilica of the Holy Sepulcher began in May 2022 and will end in 26 months thanks to an interdisciplinary team that includes archaeologists, art historians and historians, geologists, engineers and even psychologists, but also PhD students and students , who have the opportunity to make their first experiences in an extraordinary site.

We talk about it with the professor Giorgio Piras, director of the Department of Ancient Sciences of the University “La Sapienza”.

The Basilica of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem is a site without equal in the world. What sensations does it give you to work in a place like this?

“The Basilica of the Holy Sepulcher is a place full of history and symbols. Entering it is exciting even for a simple tourist, let alone for an archaeologist: working here with your own hands, in direct contact with the earth, is an undertaking of great emotional, as well as scientific, value “.

What is it that makes it so special, even compared to other archaeological sites linked to the history of Christianity?

“The area where we are excavating has been considered the burial site of Christ since late antiquity. Already in the fourth century, tradition and worship were so deeply rooted that Constantine decided to build a basilica dedicated to the Holy Sepulcher there. We do not know exactly how old this tradition is, but it is possible that it really dates back to the first century AD, because even before the advent of Christianity in that area there was a quarry used as a burial ground. On this point there is a strong correspondence between the archaeological traces and what is reported in the Gospels and in other written sources. Even if it is not easy to prove that Christ’s tomb was located right here, it is striking to think that we are entering the heart of such an ancient tradition ”.

Jerusalem, Basilica of the Holy Sepulcher. The dome over the tomb of Jesus. Photo Wknight94 / Israel via Wikimedia Commons

What is the goal of the excavations you are carrying out? What questions will you try to answer?

“The communities that are in charge of the custody of the Basilica have decided to restore the medieval flooring, which is currently in poor condition. For the first time in history it is possible to dig beneath the floor, which had never been removed before except for the replacement of individual stones. On these occasions, partial subsoil surveys were carried out, but never a systematic excavation like the one we are conducting today. With the most advanced methods of contemporary archeology we hope to finally be able to accurately reconstruct the history of this highly symbolic place ”.

What do you expect to find?

“The building we see today is from the Middle Ages and has undergone several renovations until the 19th century, but we know with certainty that it is located right on the area of the ancient Constantinian Basilica, of which we are already bringing to light the remains. We hope to reconstruct its structure and to find out how it was really made, something that has so far been impossible. In addition, we could find evidence of even earlier phases, for example the remains of a temple dedicated to Hadrian which we know was built here in the second century after Christ. The goal is to push us as far back as possible in time, in order to obtain a full reconstruction of the history of the place ”.

At what point are the works? Have any interesting findings already emerged?

“We started from the Rotonda, the most important part of the Basilica, where the shrine is located which according to tradition is built on the exact place of Christ’s burial. Traces of very ancient phases have already emerged: remains of the foundations and walls of the Constantinian Basilica have been found, and we have discovered that those who built it in the 4th century first leveled the ground with debris. Fragments of pottery and decorations presumably dating back to the same period have emerged. Later we will date the finds piece by piece, because the Romans often used waste material to build and this could reserve some surprises ”.

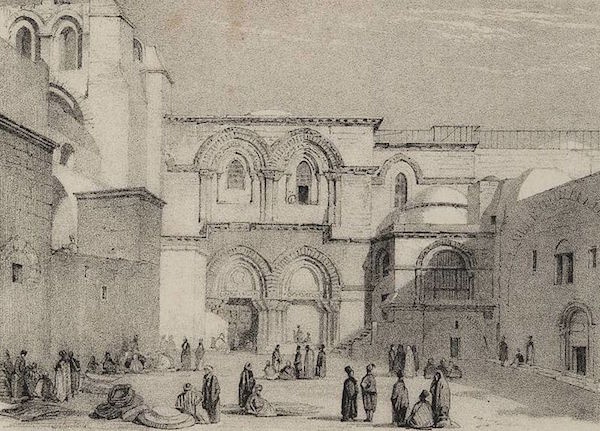

The exterior of the Basilica of the Holy Sepulcher in 1841, from Travelers in the Middle East Archive (TIMEA). Photo Hamerton, RG via Wikimedia Commons

What are the challenges of digging into a site like this?

“The greatest difficulty lies in guaranteeing full accessibility to the Basilica, as we have been asked by the communities that have it in custody. Our research will never stop pilgrimage and worship. So we work by zones: we dig in one area and then cover, to continue with the next area. We dig night and day, and in some places we will work under the walkways that will allow the passage of pilgrims, with the utmost respect for a place that is sacred to billions of people. Furthermore, having to recover very different phases chronologically, with constructions that overlap over time, makes the intervention even more complex ”.

Yours is an interdisciplinary team with a wide range of professionals, including some psychologists. How come?

“Jerusalem and the Basilica of the Holy Sepulcher itself are knots of complex political-religious tensions. It is a situation that can generate stress, especially in the youngest: PhD students, postdocs and students in their early twenties with whom we share this extraordinary experience. This is the reason for the presence of psychologists. The bulk of the team is actually made up of archaeologists from the Department of Ancient Sciences, flanked by geology technicians and static engineers. The restoration of the floor stones, on the other hand, will be carried out by the Venaria Reale of Turin with strictly conservative criteria: the stones no longer usable will be replaced with local material, the same that was used in the Middle Ages, and for the installation we will make use of workers of the place”.

The history of the Basilica is traversed by an intertwining of conflicts, negotiations and interreligious relations. How does archeology relate to the communities that own the site?

“We are on excellent terms with all three major communities – Catholic, Orthodox and Catholic-Armenian – who run this place on the basis of the Status Quo, an agreement that dates back to the mid-nineteenth century. Working in the Basilica of the Holy Sepulcher requires extreme attention to even the simplest gestures, because there is a consolidated tradition to be respected. Even a stone or a nail here takes on particular meanings, because they are linked to one or the other community. Finally, it is necessary to involve all the communities on an equal basis. We are well aware of this and we try to do it with the utmost sensitivity ”.

Basilica of the Holy Sepulcher, Jerusalem. Photo by Matanya via Wikimedia Commons