Vanessa Bell, Leonard Woolf1940, Oil on canvas, 64.8 x 81.3 cm, London, National Portrait Gallery, gift of Marjorie Tulip (‘Trekkie’) Parsons, 1969 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Until 12 December that cenacle in which new forms of life and thought took root that would change Victorian principles and the strong patriarchal spirit that the twentieth century was still imbued with, will revive in Rome thanks to the exhibition Virginia Woolf and Bloomsbury. Inventing Lifea project of the National Roman Museum and the Electa publishing house, created in collaboration with the National Portrait Gallery in London.

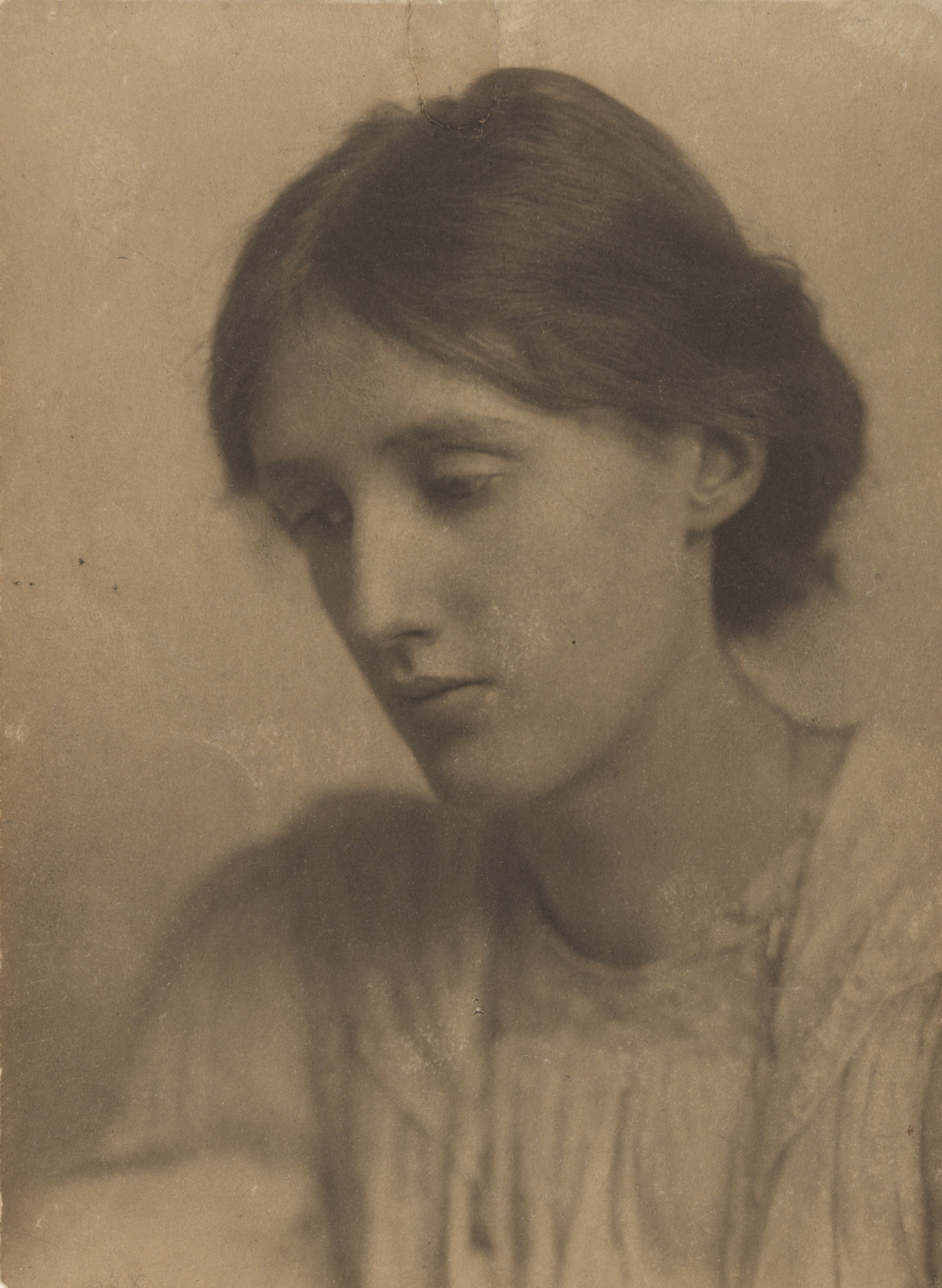

George Charles Beresford, Virginia Woolf, 1902, vintage instant print, 10.8 x 15.2 cm, London, National Portrait Gallery © National Portrait Gallery, London

The path, set up in the rooms of Palazzo Altemps – born as a noble house in the heart of Rome that has hosted prestigious literary salons and in the past hosted a prestigious library, as well as assisting, in whose church of Clemenza and Sant’Aniceto kept inside , at the wedding between Gabriele D’Annunzio and Maria Hardouin di Gallese in 1883 – was conceived and curated by Nadia Fusini in collaboration with Luca Scarlini.

The tale of Bloomsbury’s figures comes to life in the five “rooms” – the same ones that Virginia Woolf intended as secret, protected spaces, in which to affirm one’s identity and create one’s freedom – set up at Palazzo Altemps. And the public is invited to share with the young intellectuals who met in the Stephen sisters’ rooms those same artistic preferences, romantic relationships, innovative work experiences, social motivations.

Guests also included John Maynard Keynes, who revolutionized economic thinking by laying the foundations of the welfare state, and Roger Fry, critic and painter, who created another way of looking at and creating works of art.

But what shone was Virginia Woolf, the writer who opens up to Modernism, “the artist who, thanks to the shrewd use of language, builds worlds of vision, as painters create worlds of thought with color and brush” as Nadia Fusini writes in essay from the catalog.

Ray Strachey, Vanessa Bell, late 1920s, Oil on cardboard, 40.6 x 55.9 cm, London, National Portrait Gallery, gift of Barbara Strachey (Halpern, formerly Hultin), 1999 © National Portrait Gallery, London

If the exhibition opens with an explicit reference to Virginia Woolf’s essay published in 1929, in a section entirely dedicated to the English writer, a verse taken from Lost pains of love by Shakespeare gives its title to the room dedicated to the characters of Bloomsbury, in which excellent loans from the National Portrait Gallery in London allow you to tell the lives of these special, eccentric people. And love is perceived in the air as a creative freedom, which is expressed through decorative inventions that transform wardrobes, tables, chairs, armchairs into works of art.

Lady Ottoline Morrell, Simon Bussy, Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, 1922, vintage bromide print, 33.7 x 28.6 cm, National Portrait Gallery, London, acquired with the help of Friends of the National Libraries and Helen Gardner Bequest, 2003 © National Portrait Gallery, London

If the third section, Hogarth Press, reconstructs the history of the publishing house founded in 1915 when Leonard and Virginia Woolf decide to buy a press, Roger Fry and post impressionism lead the audience into the fourth room. The art critic, historian, painter Roger Fry made his country discover the great modern French painting. Between 1910 and 1911 he exhibited in London twenty-one Cézanne, thirty-seven Gauguin, twenty Van Gogh, including sunflowers, and again Picasso and Matisse. Virginia Woolf and many of the Bloomsbury youths recognize the revolutionary significance of those works. But Roger Fry did more. It was he who founded an atelier in 1913 under the direction of Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, a workshop where artists anonymously created beautiful objects designed to bring joy to everyday life. Unfortunately, the adventure will last only six years, broken by the war.

The last section of the exhibition, Omega Workshopsremembers these six years that changed the taste of the time during which Great Britain welcomed the suggestions of French painting and literature into design and fashion.

To tell, deepen and celebrate the fascinating history of the Bloomsbury group, the National Roman Museum and the Electa publishing house with the support of the Italian Virginia Woolf Society propose a varied program of cultural events linked to the themes of the exhibition, while Nadia Fusini and Luca Scarlini will meet the public at Palazzo Altemps in a series of appointments.